.jpg)

A Summary of the Literature

Preface

Latest reports indicate that Government funding has become the highest fundraising source for the VC sector at the European level, accounting for an average of approximately 25% of funds raised by investors in the past 5 years with a 30% peak in 2020 and an 18% low in 2021.

This has given rise to the question: What is the Government’s role in the VC market in Europe?

Existing research on the Government’s involvement with the VC market has shown that Government Venture Capitalists (GVCs) alone do not have an impact on their portfolio companies (in terms of an exit strategy, innovation and invention, employment growth and sales growth) in comparison to Independent Venture Capitalists (IVCs). However, there is an argument to be made of GVCs complementing IVCs where the mixed syndicates have a positive effect on portfolio companies which is similar to the effects produced by IVCs.

To better understand the question, we have compiled conclusions from several scientific reports that we reviewed.

Exits

A paper by Cumming, Grilli & Murtinu (2017) explores the effect of GVCs and IVCs on a successful exit strategy. In their research, they find that IVC-backed companies have a more positive exit than GVC-backed companies because GVC funds fail to spur potential growth within their portfolio companies. As a result, the impact of GVCs on exit performance is negligible.

Although the paper sheds a negative light on the "go it alone" strategy of European GVC funds, they find a positive and statistically relevant effect on the exit performance of young-tech companies when GVCs syndicate with IVCs. Both funds have access to a wide range of contacts and so forming a partnership would create a larger network than an IVC fund on their own, allowing entrepreneurial firms to perform better.

Innovation

In a study by Pierrakis & Saridakis (2017), they investigated innovation in GVC funds versus IVC funds. In their analysis, the authors used patent application as a proxy for innovation. After testing several hypotheses, they find that receiving investment solely from publicly backed VC funds reduces the probability of the company applying for a patent compared to a company that received private investments. As a result, there was a negative and statistically significant effect on GVC-backed investments and the firm’s potential to innovate. Pierrakis & Saridakis suggest that GVC fund managers may lack the skills that are essential for nurturing high-growth firms.

However, the paper reinforces the advantages of a GVC-IVC syndicate. They argue that GVCs are better connected to innovation players such as University labs, University incubators and science parks whereas IVCs have better access to financial resources and add more value to their portfolio companies. As a result, a co-investment between IVCs and GVCs may lead to higher patent activity i.e., innovation level than if there was only one type of investor involved.

Crowding In

Introduction

The role of government-backed venture capital organisations (GVCs) is not restricted to the benefits yielded by investee firms. Investment undertaken by GVCs typically aims to stimulate (or, “crowd-in”) investment from private VCs. Most existing studies have found evidence supporting the presence of GVC activity. Specifically, the studies seem to support the hypothesis that GVCs do not displace private VC (PVC) investment but strongly complement it. It is widely accepted that GVCs aim to foster innovation and entrepreneurship by bridging a finance and information gap. Thus, this article aims to highlight the benefits associated with GVCs along with the empirical evidence supporting such claims.

Literature

Bertoni, F., & Tykvová, T. (2015) explore how GVCs influence invention and innovation in Europe. From their univariate analysis, they find evidence to support that private VC has a stronger impact on invention and innovation than GVC. However, their multivariate analysis reveals that “GVCs boost the impact of independent venture capital investors (IVCs) on both invention and innovation.”

Furthermore, the impact of the level of investment is more significant than the total impact of the individual levels of investment when private VCs and GVCs co-invest. The discovery of such synergy gains emphasises the importance of GVCs and blended funding schemes, such as the EIC Fund, when fostering innovation. However, this argument is not conclusive. The journal ends with an interesting judgement, suggesting that “GVC is not the correct instrument to support invention and innovation in a region where IVC is lacking, but it is the correct instrument to use in a region where IVC is abundant.”

A paper by Brander, A. et al. (2015) examines the value of the investment that GVC-backed enterprises achieve in contrast with other enterprises. A key takeaway from the paper is that enterprises funded by both GVCs and PVCs secure more financing than purely PVC-backed enterprises, and substantially more than purely GVC-backed enterprises.

The paper by Bertoni, F., & Tykvová, T. (2015) suggests that one synergy gain from public-private co-investment is greater innovation. This paper by Brander, A. et al. (2015) posits another synergy gain: greater access to finance in later funding rounds. The regression analysis shows that enterprises that initially receive funding from both PVCs and GVCs obtain more funding in later rounds compared to PVC-backed enterprises. However, this paper goes one step further by analysing the impact of GVCs at different economic levels. Brander, A. et al. (2015) find significant evidence at a micro (enterprise) level and a macro (market-wide) level supporting the existence of synergy gains from public-private co-investment.

A study by Colombo, M. G. et al. (2016) assesses the evidence for and against the crowding-in effect. They cite more cases in which GVCs have encouraged investment by PVCs. For example, they highlight the success of Yozma Group in developing the VC market in Israel during the early nineties. Another example in the paper is the Australian Innovation Investment Fund (AIIF). THE AIIF led to a higher level of investment activity following its formation in 1997 (Cumming, D.J., 2007).

Mixed funding - between GVCs and pure Private Venture Capitalists (PVCs) - in the first funding round leads to more funding in later rounds than just pure PVC funding. On the other hand, pure GVC funding in the first round is associated with significantly less expected funding in later rounds. An additionality hypothesis can be made where enterprises that receive both PVC and GVC funding end up with significantly more funding in total than other enterprises. This can be seen at enterprise level as well as market level. (Brander et. al, 2015)

Employment and Sales Growth

Grilli & Murtinu (2014) assess the impact of GVCs and IVCs on the sales and employee growth of European high-tech entrepreneurial firms. After applying an econometric framework, they find that the government has an inability to support high-tech entrepreneurial firms by operating directly in the VC market. They suggest IVCs contribute more than GVCs in terms of the development of business ideas whereas GVCs lack the value-added skills, as well as lack the availability of financial resources, to encourage sales and employment growth. However, the authors do find a positive and statistically significant impact of syndicated investments by both types of investors on the firm’s sales growth but only when IVCs are leading. As a result, the paper concludes that public intervention should be in the form of creating a favourable environment for VC initiatives through indirect forms of support rather than a "hands-on approach".

Standaert & Manigart (2018) also evaluate employee growth within IVC-GVC syndicates. Their studies show that if IVC funds lead the mixed syndicate, their portfolio companies experience higher performance and stronger growth. The authors suggest that these syndicates are more efficient in pooling resources provided by different partners. This is because a low government ownership stake in hybrid IVCs compared to GVCs results in investment policies similar to pure IVCs without the government as an LP. Hybrid IVCs are then able to implement their own strategy and their decisions are not distorted by the objectives of the GVC. As a result, the IVC-GVC syndicates can encourage more sales growth than pure GVCs.

Key findings

"However, GVCs boost the impact of independent venture capital investors (IVCs) on both invention and innovation."

"GVC is not the correct instrument to support invention and innovation in a region where IVC is lacking, but it is the correct instrument to use in a region where IVC is abundant."

"Mixed funding in the first round is associated with more funding in later rounds than pure PVC funding."

1. Cumming, D. J., Grilli, L., & Murtinu, S. (2017).

Abstract/Introduction:

- Independent VC-backed companies have a more positive exit than GVC-backed companies.

- A mix of IVC-GVC does give a higher likelihood of a positive exit than IVC-backing alone.

- Results remain stable even after controlling for endogeneity concerns, selection bias and omitted variable bias.

- Econometric studies have showed that GVC backed companies follow the similar growth patterns as those who did not receive any government backing.

- IVC funds are more effective at spurring growth in portfolio companies.

- However, there is a lack of empirical evaluation of the performance of the mix of IVC-GVC from an investor’s point of view.

- The impact of GVCs on the exit is negligible.

Analysis:

- Why do GVCs perform worse than IVCs?

- GVC agreements are determined by regulators and do not resemble the agreements used by IVCs. These GVC agreements do not vary over time and across fund managers which make them less efficient than IVCs.

- GVCs believed to have less efficient compensation terms relative to IVCs. They are comparatively invariant across managers and funds as well as over time. As a result, GVCs face employee retention among better fund managers as they receive better outside offers.

- GVCs have a lack of independence in decision making.

- GVCs face political pressure to not fire founding entrepreneurs and risk political problems if they do so.

- GVCs face pressure to pursue non-financial related goals such as employment maximisation.

- Why do a mix of IVC-GVC syndicates work?

- The investee firm financed by GVCs enjoy the same structural advantages as the IVCs do (clauses in the agreements mitigate agency problems in order to facilitate maximisation of investee returns and investee performance).

- They enjoy the compensation terms of an IVC. The inefficient compensation terms of GVCs are significantly mitigated.

- They face no political pressure and so decision making is completely independent.

- ‘GVCs would be expected to have access to governmental contacts that may be beneficial to the entrepreneurial firm, which could include government-related suppliers and customers, and enable stream-lined and faster regulatory approval of business matters that are in the entrepreneurial firm's interest.’ (p.4)

- Allowing GVC-IVC partnership to have access to larger contacts and network than a IVC syndicated would. Entrepreneurial firms can perform better.

Conclusion:

- Findings shed a negative light on the ‘go it alone’ strategy of European GVC funds.

- However, positive economically and statistically relevant effect on exit performance of young high-tech companies when government bodies syndicate with IVCs (names Horizon 2020 as an example).

- Leads to a principal-principal conflict (heterogenous investors have different objectives to the institution).

- ‘Government and the independent venture capital investor should always remind to keep the institutional heterogeneity of the syndicate at a manageable level in order to limit negative side-effects.’ (p.19)

2. Grilli, L., & Murtinu, S. (2014).

Abstract:

- Positive and statistically significant impact of syndicated investments by both types of investors on the firm’s sales growth only when the IVC is leading.

- ‘Doubt on the ability of governments to support high-tech entrepreneurial firms through a direct and active involvement in VC markets.’ (p. 1)

Analysis:

- IVCs contribute more than GVCs in terms of development of business ideas, managerial professionalisation, and exit orientation.

- GVCs show a less-risk adverse attitude in investment decisions as they value social benefits that their selected targets bring in.

- GVCs investment decisions may be subject to distortions and imperfections.

- Justification for syndication and co-financing (comes from willingness of VCs):

- Reduce information asymmetries in the screening process as VCs provide a ‘second opinion’.

- Overcome capital constraints and take advantage of complementary resources, skills, networks, and industry expertise of different VCs.

- Diversify investments and reduce overall portfolio risk.

- Reduce agency problems with entrepreneurs.

- Signal to capital markets the quality of focal VC syndicate-backed firm and influence likelihood of successful exit.

- However, there is a lack of literature that evaluates the effectiveness of these mixed syndicates.

- France has the largest share of GVC backed firms (20.08%) followed by Spain (17.99%)

- France also has the largest share of co-financing between IVCs and GVCs (31.75%) followed by the UK (15.87%).

- Co-finance investments mainly targeted software (41.27%) and biotech (24.60%) firms.

- 59% of co-finance investments was a syndication between IVCs and GVCs.

- After applying an econometric model, there is evidence of a positive moderating role of GVC on the employment growth of IVC-backed firms.

Conclusion:

- Notable presence of VC funds directly managed by government bodies compared to the US.

- GVC does not have an impact on sales and employee growth of European high-tech entrepreneurial firms.

- Performance of syndicated-backed firms increases if GVC has a minority role rather than when they are leaders.

- Negative light on government’s ability to support high-tech entrepreneurial firms by operating directly in the VC market.

- Public intervention should create a favourable environment for private VC initiatives through indirect forms of support rather than a ‘hands-on-approach’.

- ‘Our analysis suggests that the inefficacy of GVCs in fostering the (sales) growth of European high-tech entrepreneurial firms is not only related to the scarce availability of financial resources but also might be due to a lack of value-added skills.’ (p.15)

3. Pierrakis, Y., & Saridakis, G. (2017).

Abstract:

- Receiving investment solely from publicly backed VC funds reduces the probability of the company to apply for a patent compared to a company that received private investments.

- However, the probability of companies that have a mix of private and public does not greatly differ from companies that just get investments from private VC funds.

- Stresses the importance of co-investments between publicly backed and private venture capital funds to promote innovation.

- Public intervention increases supply of finance for businesses seeking equity finance.

- Public sector has become increasingly important as an investor in absolute and relative terms.

- Enterprises with moderate government VC support outperform with only private VC support and those with extensive government support (in terms of value creation and patent creation).

- GVCs on their own have no impact on invention and innovation but, when partnered with IVCs, the impact is larger.

Analysis:

- Hypothesis: GVC funds are more likely to affect patents when they co-invest together with PVC funds.

- GVCs have a wider outreach and are better connected with regional innovation players such as University labs, University incubators and science parks than PVCs.

- PVCs have better access to financial resources and add more value to the portfolio companies.

- Therefore, patenting activity is higher when GVCs and IVCs co-invest than when companies have only one investor type.

Conclusion:

- There is a statistically significant and negative effect of GVC backed investments and the firm’s potential to innovate.

- This relationship exists due to some unmeasured investment characteristics or environment in which funds operate.

- Venture capitalists from publicly backed funds may lack the skills required for nurturing high growth ventures.

4. Standaert, T., & Manigart, S. (2018).

Abstract:

- Companies backed by hybrid IVC funds creates more jobs than hybrid captive or hybrid GVC funds.

Analysis:

- When governments invest in syndicates led by independent VC funds, their portfolio companies experience higher performance and stronger growth.

- Mixed syndicates seem to be more efficient in pooling resources provided by different partners.

- A low government ownership stake in hybrid IVCs compared to GVCs leads to investment policies that are similar to pure IVCs without the government as a LP.

- Hybrid IVCs are able to implement their own strategy and it is not distorted by objectives of a minority government LP.

- The role of the government as a LP is limited to enlarging the pool of funding.

- Hybrid IVC funds participate in larger funding rounds (median: €3 million) compared to GVCs (median: €1.1 million).

Conclusion:

- Hybrid IVCs allow employment growth.

- Provides companies with superior monitoring and value adding services with the objective of realising a successful exit.

- Delegating VC processes to independent VC managers is beneficial for job creation and ensuing economic development in the region.

- Delegating VC processes to a government official will be less efficient.

- Hybrid IVC funds are managed by young VC partnerships. …

- If the government acts as a LP in independent VC funds managed by young VC teams, they contribute to employment creation as well as stimulating and broadening the VC industry

5. Bertoni, F., & Tykvová, T. (2015).

Abstract:

- Paper explores whether and how governmental venture capital investors (GVCs) spur invention and innovation in young biotech companies in Europe.

- Findings indicate that GVCs, as stand-alone investors, have no impact on invention and innovation.

- However, GVCs boost the impact of independent venture capital investors (IVCs) on both invention and innovation.

- Conclude that GVCs are an ineffective substitute, but an effective complement, of IVCs.

- Distinguish between technology-oriented GVCs (TVCs) and development-oriented GVCs (DVCs).

- Find that DVCs are better at increasing firm’s inventions, and that TVCs, combined with IVCs, support innovations.

Analysis:

- Aim to answer the question: Have these [innovative] funds been successful in supporting inventions and innovations in Europe?

- Univariate analysis: Results may suggest that GVC-backed companies focus on exploratory activity, but that their patents are of a low commercial use (i.e., they are inventions that rarely become innovations).

- IVC backing is associated to more inventions and innovations than GVC backing and the differences in simple patent counts and citations are statistically significant.

- Supports the hypothesis that IVC has a stronger impact on invention and innovation than GVC.

- Multivariate analysis: Run 5 models

- Model 1: Focuses on differences between companies financed by an IVC, companies financed by a GVC and non-VC-backed companies.

- The coefficient of the GVC dummy is insignificant. GVC-backed companies do not have a higher patenting activity than non-VC-backed companies.

- Find a positive and highly statistically significant effect for IVCs.

- F-test suggests that the IVC-effect is significantly higher than the GVC-effect. Evidence that GVC-backed companies underperform IVC-backed companies in terms of inventions.

- Model 2: Test whether TVC-backed companies outperform DVC-backed companies.

- DVC-backed companies outperform TVC-backed companies.

- Model 3: Investigate whether syndicates between IVCs and GVCs increase patenting.

- Find that GVCs and IVCs complement each other.

- When they syndicate, the observed effect is larger than the sum of the effects of the two investors on a stand-alone basis and is statistically and economically highly significant.

- GVC is not the correct instrument to support invention and innovation in a region where IVC is lacking, but it is the correct instrument to use in a region where IVC is abundant.

- Model 1: Focuses on differences between companies financed by an IVC, companies financed by a GVC and non-VC-backed companies.

Conclusions:

- GVC has, on average, no impact on invention and innovation.

- IVC-backed companies patent more than both non-VC-backed and GVC-backed companies.

- Evidence suggests that GVC is a poor substitute for IVC.

- Interesting finding: GVC is an effective complement for IVC.

6. Brander, J. A., Du, Q., & Hellmann, T. (2015).

Abstract:

- Article examines enterprises funded by government-sponsored venture capitalists (GVCs).

- Find that enterprises funded by both GVCs and private venture capitalists (PVCs) obtain more investment than enterprises funded purely by PVCs, and much more than those funded purely by GVCs.

- Markets with more GVC funding have more VC funding per enterprise and more VC-funded enterprises, suggesting that GVC finance largely augments rather than displaces PVC finance.

- Positive association between mixed GVC/PVC funding and successful exits, as measured by initial public offerings (IPOs) and acquisitions, attributable largely to the additional investment.

Analysis:

- Aim to answer question: Does GVC finance crowd out (replace) private venture capital (PVC) finance or does it provide additional finance?

- Regression analysis: Treat first-round investment received by an enterprise as the dependent variable. Distinguish between enterprises that have three different financing mixes: private (default), mixed and public. Test following hypothesis: whether GVC investment crowds out PVC investment.

- Panel A: Find that enterprises with pure GVC funding receive much less total investment than those with pure PVC funding.

- Results are statistically highly significant.

- Economic effects appear to be substantial.

- Mixed funding in the first round is associated with more funding in later rounds than pure PVC funding.

- Pure GVC funding in the first round is associated with significantly less expected funding in later rounds.

- Evidence suggests that the average investment per investor is lower for GVC-backed enterprises (both GVC-Mix and GVC-Pure).

- Even though individual investors invest less on average in the presence of GVC investors, the increase in the number of investors more than compensates for this, resulting in an overall higher level of investment in GVC-Mix deals.

- Panel B: Presence of GVC funding in the first round has a strong positive effect on later round

- Presence of first round GVC activity is associated with more PVC investors

- GVC funding adds to the total funding pool rather than just displacing private investment.

- Enterprises with mixed funding do not experience lower funding from PVCs.

- Suggests that, rather than crowding out PVC funding, GVC funding may well act as a catalyst that attracts more PVC funding to an enterprise.

- Enterprises with pure GVC funding receive much less investment than other enterprises (with fewer investors, and also less investment per investor).

- Panel A: Find that enterprises with pure GVC funding receive much less total investment than those with pure PVC funding.

- Market-level analysis:

- GVC market investment appears to have a positive effect on overall market investment, on the number of enterprises, and on the number of investors per enterprise.

- Conclude that the evidence at the market level does not support the crowding out hypothesis, but instead favours the additionality hypothesis (enterprises that receive both PVC and GVC funding end up with significantly more funding in total than other enterprises.)

Conclusion:

- Significant evidence supporting additionality – at enterprise level and market level

- When GVCs syndicate (coinvest) with PVCs they act primarily to increase the amount of financing received by the enterprise and do not significantly displace PVC financing for that enterprise.

- GVC activity of this type expands available finance.

7. Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2016).

Abstract:

- Paper documents the evolution and to compares the effects of the different types of governmental support.

- There have been successful GVC initiatives, such as the Australian Innovation Investment Fund.

Analysis:

- Evidence supporting crowding-in:

- In Israel, the Yozma Group was launched in 1993 using public funds.

- Yozma is widely considered to be the catalyst for the successful development of the domestic VC industry in that country.

- Similarly, governmental support, particularly the IIF program, has been very helpful in Australia.

- Establishment of the IIF program in 1997 led to more investments in subsequent years, even after the collapse of the Internet bubble (Cumming 2007).

- Brander et al. (2014) find that markets with more GVC funding have more VC funding per enterprise and more VC-funded enterprises, suggesting that GVC finance largely augments, rather than displaces, private VC finance.

- Further evidence of crowding-in effects comes from Hood (2000), who showed that the Scottish public VC program SDF was followed by the formation of new private VC funds.

- In Israel, the Yozma Group was launched in 1993 using public funds.

- Evidence against crowding-in:

- Bertoni et al. (2014b) show that although European governments have tried to fill the seed investment gap left by private VC investors, by launching GVC funds (e.g. university seed and regional government-controlled funds) and investing in small, young, seed-stage companies, notably biotech firms, they have failed to attract private VCs to these companies.

Conclusion:

- Global empirical evidence is mixed; good examples, such as the Australian IIF, are in contrast with a lack of success of GVC programs in other countries.

8. Croce, A., Martí, J., & Reverte, C. (2019).

Abstract:

- Analyse whether young entrepreneurial ventures backed by different types of venture capital firms, i.e., private (PVCs) vs. government-owned (GOVCs), experience higher employment growth than a matched control group of non-venture-backed companies and whether this effect is particularly relevant in a period of crisis.

- Results show that PVCs exert a higher impact on employment growth in invested companies than GOVCs in investments carried out during a period of crisis whereas the opposite is found in the case of investments completed before the crisis.

- Find that PVCs enhance their job-creation performance during a period of crisis while GOVCs significantly reduce their impact on employment in the investments carried out during the crisis.

Hypotheses:

- H1: Entrepreneurial ventures backed by GOVCs do not show a significantly different employment growth than those backed by PVCs in a period of normal economic activity.

- H2: Entrepreneurial ventures backed by PVCs during a period of crisis show higher employment growth than those backed by PVCs in a period of normal economic activity.

- H3: Entrepreneurial ventures backed by GOVCs during a period of crisis show lower employment growth than those backed by GOVCs in a period of normal economic activity.

- H4: Entrepreneurial ventures backed by GOVCs show lower employment growth than those backed by PVCs in the case of investments carried out during a period of crisis.

Analysis:

- Cross-section analysis: Analyse the difference in average employment growth of investee companies 3 years after versus 3 years before the event (crisis).

- Panel A: The results clearly indicate that the estimated coefficients of VC variables are positive and statistically significant.

- These results support the expectation that VC investments boost employment growth in the treated companies.

- Presence of PVCs on average generated between 239 and 6.362 jobs and the presence of GOVCs generated between 7.491 and 10.557 jobs in investee companies in the 3 years following the investments carried out before the crisis started.

- Presence of PVCs investors generated between 732 and 8.814 jobs and the presence of GOVC investors between 2.486 and 5.530 jobs in the 3 years following the investments in the case of companies funded after the onset of the crisis.

- “Additional” effect of syndication on employment growth and is not significant.

- Find that the amount financed has a positive effect on employment growth.

- Panel B: Compare the effect of PVCs with that of GOVCs.

- Employment growth in companies invested by PVCs is significantly lower than that of those backed by GOVCs (in normal times).

- Panel C: Compare the effect of the crisis on the impact of VC investments.

- Find that the impact of PVCs on employment growth is significantly higher in investments carried out during the crisis than in those completed before the crisis (i.e., around 2.5 workers more).

- The effect is significantly reduced in GOVCs (i.e., around 5 workers less), thus confirming H2 and H3.

- Find that PVCs have higher impact than GOVCs in fostering employment growth of invested companies (i.e., around 3 workers more), in the case of investments completed during the crisis.

- Providing support to H4.

- Panel A: The results clearly indicate that the estimated coefficients of VC variables are positive and statistically significant.

Conclusion:

- Results reveal that the investments of GOVCs have a higher impact on employment growth than those of PVCs in a period of normal economic activity, which is not what we expected according to our H1.

- Companies backed by PVCs during the crisis grow significantly more that those funded before the onset of the crisis whereas the opposite is observed in the case on companies backed by GOVCs.

- This is in accordance with H2 and H3.

- Confirm that companies backed by PVCs during a period of crisis grow more than those backed by GOVCs, thus confirming H4.

9. Cumming, D. J., & MacIntosh, J. G. (2006).

Abstract:

- Examine a Canadian tax-driven venture capital vehicle known as the “Labour Sponsored Venture Capital Corporation” (LSVCC).

- These are essentially a type of highly specialized mutual fund, open to individuals at all points on the economic spectrum.

- Invest in small entrepreneurial companies.

- Empirical analysis of our data (which covers the 1977–2001 period) is highly consistent with crowding out.

- These are essentially a type of highly specialized mutual fund, open to individuals at all points on the economic spectrum.

- Data suggest that crowding out has been sufficiently energetic as to lead to a reduction in the aggregate pool of venture capital in Canada.

Analysis:

- Central question: Are the tax advantages conferred on LSVCCs have resulted in LSVCCs “crowding out,” or displacing other types of venture capital funds?

- Multivariate analysis:

- Finding of a positive coefficient for LSVCCs would indicate LSVCCs have increased the aggregate pool of capital, while an insignificant coefficient for LSVCCs signifies 100% crowding out (i.e., the replacement of private VCs with LSVCCs), and a negative and significant coefficient indicates more than 100% crowding out (i.e., a reduction in the aggregate pool of capital).

- The coefficients for the federal LSVCCs are mostly insignificant.

- These results are consistent with the view that both the provincially and federally incorporated LSVCCs have crowded out other forms of venture capital funds, resulting in no overall increase in the pool of venture capital in Canada.

Conclusion:

- Empirical evidence suggests that the LSVCCs have not met their goal of expanding the pool of venture capital

- May have led to some contraction.

- The federal LSVCCs have so energetically crowded out other funds as to lead to an overall reduction in the pool of venture capital.

- The coefficients for this dummy suggest that the existence of federal LSVCCs has led to 400 fewer investments per year on a Canada-wide basis.

- Represents approximately $1 billion per year in value.

- Suggest that this crowding out is a natural consequence of the tax advantage of the LSVCCs since it lowers the required rate of return (hence, can outbid other funds).

- The coefficients for this dummy suggest that the existence of federal LSVCCs has led to 400 fewer investments per year on a Canada-wide basis.

10. Karsai, J. (2017).

Abstract:

- Venture capital (VC) sector in central and eastern Europe (CEE) is characterised by the dominance of public resources.

- This is mainly due to a new type of equity scheme introduced in the European Union’s 2007–2013 programming period.

- Paper examines how successful the CEE EU member states, with a relatively less developed VC industry, were in using government equity schemes based on market cooperation between public and private market actors. It provides a general overview of the VC programmes launched in the CEE region viewed through the lens of academic design theories.

- Paper concludes that government VC programmes in the region are characterised by short time frames, administrative requirements which restricted investors, small fund sizes preventing efficient operation and limited participation of institutional investors.

- Compared to developed countries agency problems were much more pronounced.

- The limited number of business angels and incubator organisations, the high number of underfinanced promising start-ups and the misuse of government connections meant that the use of predominantly hybrid funds’ forms of government VC programmes were more challenging in the CEE region compared to western Europe.

- However, the greatest risk of public equity schemes – the crowding out effect on private investors – is absent in the CEE region because of the lack of private investors.

Analysis:

- Purpose of paper: to answer the question of “how successful the use of EU funds for VC purposes in the CEE region has been, a region that has a weakly developed VC market, and to what extent the lessons of earlier public equity schemes in countries with more advanced VC sectors can be exploited.”

- Addressed these questions by examining the government’s role as an investor in VC markets through a detailed overview of the magnitude, forms and features of public participation, including the frequently used organisational and incentive structures employed in hybrid VC funds, using examples from the CEE countries.

Conclusion:

- Based on the market principle, in the framework of the government VC programmes arranged by CEE managing government authorities it was the market that determined investments in accordance with the relevant EU regulations.

- However, the invited private investors were mostly inexperienced compared to their western peers.

- The CEE VC programmes financed by EU funds were highly over-engineered. Incumbent fund managers (investors) were reluctant to follow regulations, while inexperienced authorities executed virtually no control on their compliance of regulations.

- Long set-up times were especially prevalent in the CEE region’s programmes as a consequence of the exhausting regulation system and inexperience of actors. The shorter period available for investing resulted in hasty investment decisions, poor selection of projects and thus inefficient investments

- The VC funds that were created in the CEE region were too small, mainly as a consequence of the restrictive state aid rules and the VC guidelines that were in place for the most part of the programming period.

- Agency problems were much more pronounced in the CEE region compared to the more developed markets. Potential misuse of government funds could be attributed partly to the regulatory capture when selecting the fund managers to the programmes, and partly by over-incentivising the private investors of the hybrid funds.

- Thorough evaluation of the programmes was not initiated by the respective managing authorities in the CEE either during or after the programmes. In fact, no one took the initiative to devise an appropriate database for the evaluation of these programmes at the very start of this process.

1. Owen, R., North, D., & Mac an Bhaird, C. (2019).

Abstract:

- Investigate the effectiveness of government backed venture capital schemes (GVCs) in funding early stage entrepreneurial ventures.

- Addressing fundamental issues of additionality, crowding out, economic impact and sustainability, we discover that UK GVC-backed schemes have evolved to provide more effective, targeted, funding for high growth potential firms.

- Combining primary data from a number of sources, we discover positive impacts of increases in turnover and employment in funded ventures, along with effective targeting of specific funding gaps.

- Issues remain, including a lack of liquidity in follow-on funding and a requirement for longer time horizon in funds, as firms typically fall behind in development schedules.

- A need for greater flexibility in GVC-backed funds. Policy designers should be cognisant of the changing external financing ecosystem when designing co-investment schemes.

%20Table%201.png?width=750&name=Owen%20et%20al.%20(2019)%20Table%201.png)

Analysis:

- Q1: Are schemes meeting specific gaps in the UK entrepreneurial finance market? Finance escalator theory suggest there is a gap requiring specific types of GVC scheme interventions, notably early stage and long horizon R&D investment (Baldock, 2016).

- The 16 UKIIF recipients sought between £75,000 and £10.4m (median £2.4m), demonstrating demand for early stage longer horizon R&D equity finance at beyond the EU state aid cap of £2m at the time of funding, supporting the Rowlands gap (2009) hypothesis and subsequent findings of Baldock et al (2015).

- Q2: Are schemes adding value and avoiding duplication or crowding out of the private sector (Lerner, 2010, Leleux and Surlemont, 2003)?

- Overall there was little or no evidence from the management surveys of funding duplication either between public funding, or in crowding out private funding (see additionality measures below), particularly as the businesses “required funding within certain time parameters, crucially in order to retain market primacy”, typically within a 6-12 months period (Baldock and Mason, 2015).

- Q3: What early stage economic impacts are the schemes making? What evidence is there to support Lerner’s (2010) contention that GVCFs can make a difference to business growth and innovation?

- Our ACF study found that two thirds of the 15 assisted businesses subcontracted work out, with a median of five jobs created and an average across the businesses of 3.3 jobs.

- Our studies of ECF and ACF also demonstrated that the vast majority of assisted businesses had raised their levels of innovation. ECF recipients exhibited high proportions improving products, services, marketing and business processes (all 75% or higher), whilst over half of the ACF firms had introduced new or improved patents and copyrights.

- Q4: How well adjusted are schemes to the lengthening exit timetables experienced post GFC (Axelson and Martinovic, 2012)? Do they have the flexibility and follow on funding capability (Cumming, 2011) which Lerner (2010) advocates for long game investment?

- Table 7 demonstrates that at the time of the initial early assessment survey, typically one year after funding, approximately one fifth of assisted businesses were slipping behind their planned development schedules.

- Our ACF study in 2014 indicates one third were already behind schedule. However, when we look at the longitudinal performance, we find that a further year on UKIIF businesses have slipped back (from 15% to 28% being behind schedule).

- Three years further on the majority of surveyed ECFs have fallen behind schedule, resulting in a median rise of 1.5 years in their estimated exit timetables (rising from 5 to 6.5 years).

- Q5: Do schemes have the size and scale to make a lasting legacy impact on the early stage entrepreneurial finance market in the UK? Lerner’s (2010) ultimate aim is for GVCFs to catalyse private VC entry and create a sustainable VC ecosystem.

- It is clear that meeting the follow-on funding ‘series A-B’ scale funding is critical to maintaining portfolio business development trajectories and associated market primacy objectives of what are essentially highly innovative and market leading businesses with high growth potential.

Conclusion:

- Our finding that project additionality is relatively greater than financial additionality over similar time and size scales suggests that traditional conceptions and assumptions about crowding out are overly simplistic, and that GVC schemes enable firms to respond to investment opportunities faster than they would otherwise.

- This is particularly important in the post GFC environment, given the significantly altered funding landscape.

- Similarly, we find that the ‘financing gap’ addressed is not standardised but varies according to requirements and preferences of entrepreneurs. Each scheme is tailored to provide investment for a different type of ‘funding gap’.

- In this context, it is interesting to observe that GVC schemes have evolved and adapted to address the many and various requirements of early stage ventures.

- In addressing scheme design, policy makers should consider whether funding ceilings are significantly high to adequately serve the market, and more importantly enable greater scale by facilitating second funds within a limited time cycle. Investors and policy makers need to ensure early exit sales are avoided.

- This will involve ensuring sufficient liquidity in exit markets by developing follow-on funding, and extending the timeline to exit, particularly for ECFs.

- To achieve this, schemes require greater inbuilt flexibility along with more developed exit strategies.

Visual Summary

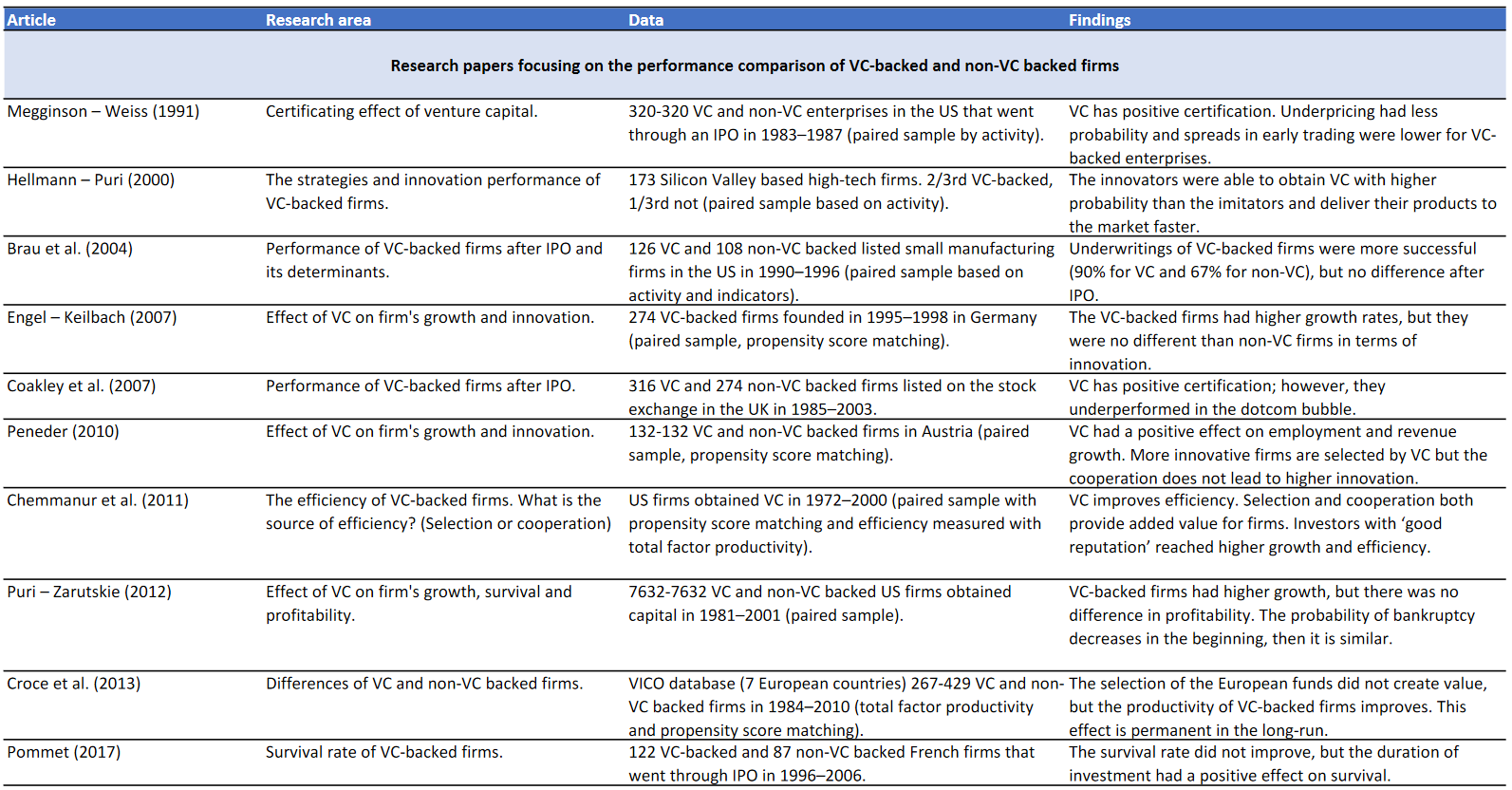

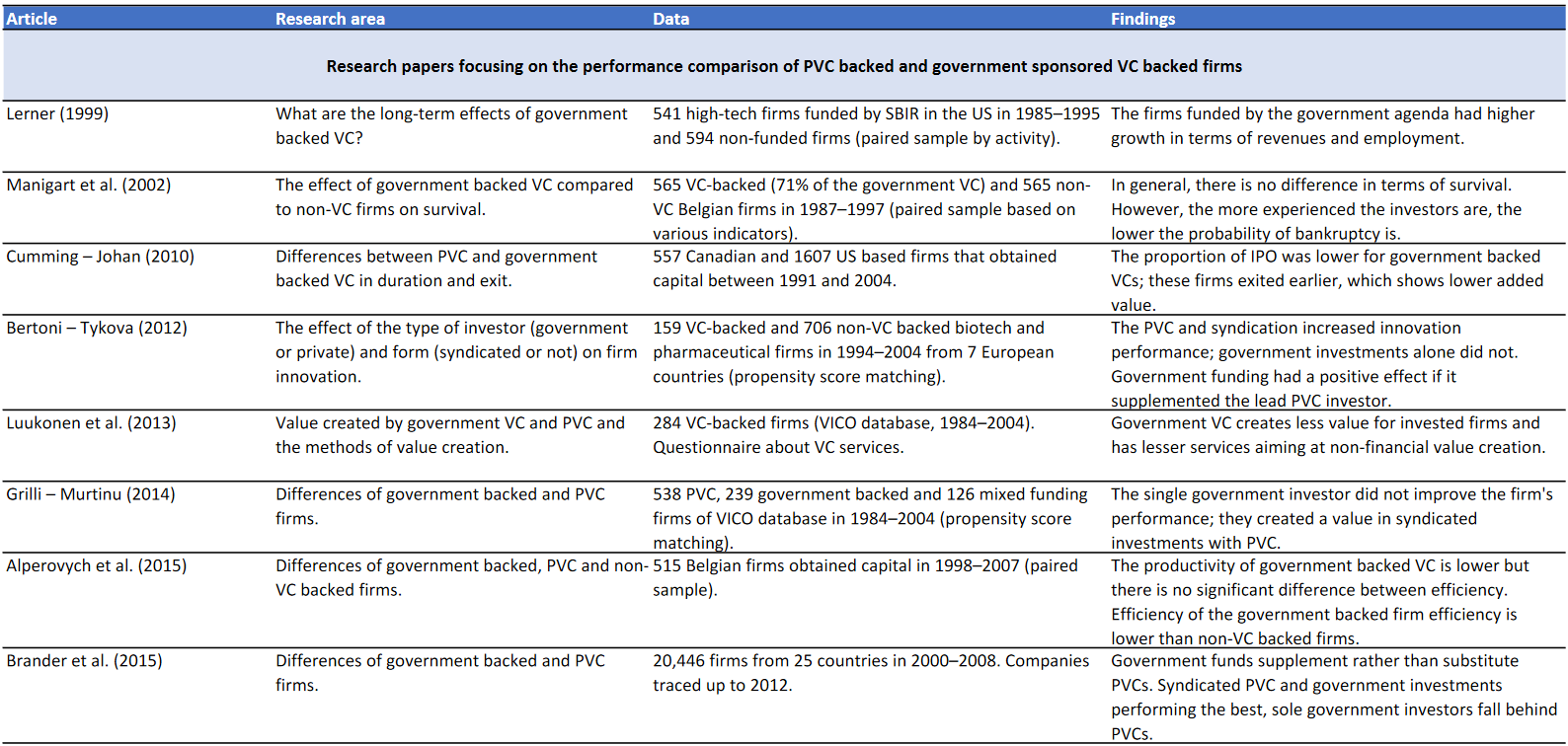

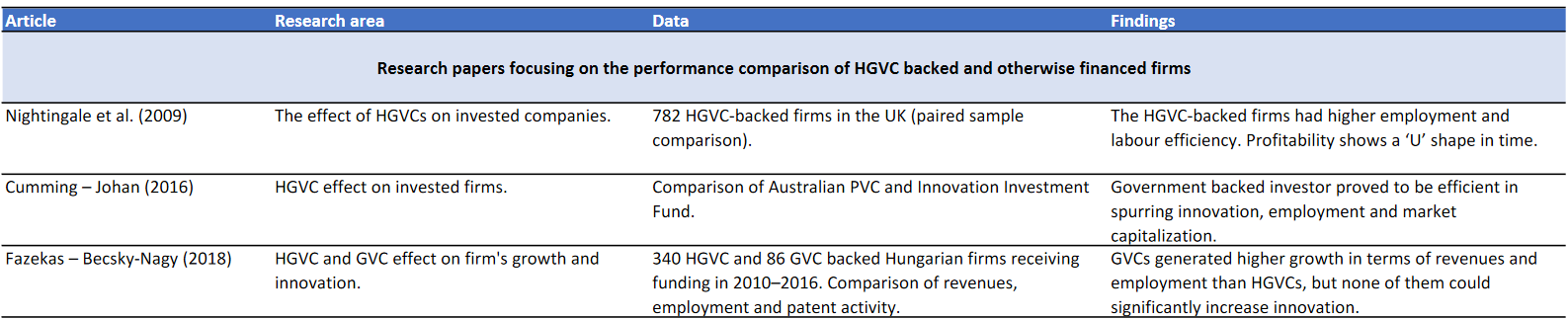

Source: Fazekas, B., & Becsky-Nagy, P. (2021). A new theoretical model of government backed venture capital funding, Acta Oeconomica, 71(3), 487-506. Table 1.

References

- Bertoni, F., & Tykvová, T. (2015). Does governmental venture capital spur invention and innovation? Evidence from young European biotech companies. Research Policy, 44(4), 925-935.

- Brander, J. A., Du, Q., & Hellmann, T. (2015). The effects of government-sponsored venture capital: international evidence. Review of Finance, 19(2)

- Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2016). Governmental venture capital for innovative young firms. The Journal of Technolo

- Croce, A., Martí, J., & Reverte, C. (2019). The role of private versus governmental venture capital in fostering job creation during the crisis. Small Business Economics,

- Cumming, D. J., & MacIntosh, J. G. (2006). Crowding out private equity: Canadian evidence. Journal of Business venturing, 21(5), 569-60

- Cumming, D. J., Grilli, L., & Murtinu, S. (2017). Governmental and independent venture capital investments in Europe: A firm-level performance analysis. Journal of corporate fi

- Grilli, L., & Murtinu, S. (2014). Government, venture capital and the growth of European high-tech entrepreneurial firms. Research Po

- Pierrakis, Y., & Saridakis, G. (2017). Do publicly backed venture capital investments promote innovation? Differences between privately and publicly backed funds in the UK venture capital market. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 7, 55-64.

- Standaert, T., & Manigart, S. (2018). Government as fund-of-fund and VC fund sponsors: effect on employment in portfolio companies. Small Busines

- Karsai, J. (2017) Government venture capital in central and eastern Europe, Venture Capital, 20:1, 73-102

- Owen, R., North, D., & Mac an Bhaird, C. (2019). The Role of Government Venture Capital Funds: Recent lessons from the UK experience.

At Winnovart, it is part of our mission to bridge the gap between stakeholders of the grants-funding market-space across Europe. We believe in the potential of grants to create ecosystems that drive innovation, growth and reduce disparities between the regions of Europe. Our aim is to support innovative SMEs, private investors and funding agencies to become part of this ecosystem and make the most of it.

Our presence in Western, Eastern and Northern Europe enables us to create international business cases for our clients, in the context of attractive funding programmes as well as beyond it, by opening up international development opportunities.

For more updates on funding opportunities, please follow us on social media: Facebook, Linkedin or Twitter.

|

For more details about Winnovart please check our website. If you would like to be contacted by our experts please reply to

office@winnovart.com or contact us here and we will get in touch very soon.

|